(Apologies for the delay with this review – I’ve been filling out a job applications again and coppicing!)

Before I shoehorn my book review in, I might as well confront the daily prompt: What do I complain about the most?

Ironically, it is AI at the moment. I understand that it can be used as a tool to help people with research, but relying on automation in life takes the fulfillment out of it. What we want is to be happy in our jobs, not to have machines replace them. And don’t even get me started about how it depreciates people’s creative abilities!

I might be a rubbish blogger, but at least I wrote and corrected this article by myself. Screw you [“””improve”” with AI] function!

Besides, Chat GPT wouldn’t be able to pick up on the books I’ve found myself and certainly wouldn’t reference them correctly!

History is, for the most part, written by the victors regardless of subject or philosophy. Most classical books we teach and recommend today are a lucky draw from the most competent and at least most charismatic authors of the era’s standards. Sure, the values of it’s backers don’t forever persist with the passage of orbit; nobody today reads Rudyard Kipling’s shorts to appreciate the pinnacles of Imperial Bravado, nor attend Wagner purely on buoyancy of his production’s antisemitic undertones.

Well-er, some probably do and always will.

Some classics fall out of favour and die. The opposite is possible. Some obscure pieces clinging to memory by the skin of their covers are catapulted into newfound glory by the hook of newfound resonance: Mary Shelley’s Last Man got something of an Indian Summer around Lockdown due to it’s coincidential description of a vicious pandemic in an alternative twenty-first century. Aphra Behn, formerly a neglected poet, has had her reputation revitalised during the later 20th century for her early abolutionist play “Ooronoko” (1688).

Hell, the other year everyone was going crazy about Cormack Maccarthy’s “Blood meridian” because a horror youtuber reviewed it, pitting the titular antagonist Judge Holden against a certain hateful computer in a sin measuring contest!

But some works do not catch on, no matter how wealthy the publisher or high-ranking their fans may be…

Main overview – Allusions to Muffins and suicide.

I first heard about Frederick Howard’s juvenilia when reading through the “Life of Samuel Johnson”. Boswell thought fit to note that the famous critic was frequently impressed by the young courtesan’s poetry. I mean young; Fred inherited his father’s position as the earl of Carlisle at the rotten age of ten years old! Aside from Johnson’s clubbers, the earl had a very rich cast of associates – ranging from the troubled whig Charles James Fox to the deranged Necrophilliac George Sellwyn.

After the curious anecdote of the man who shot himself over Muffins1 and Sammy’s apoleptic raging about American hypocrisy, Johnson’s biography includes a small letter dated 28/11/1783 (pp 1255 – 1256) – the earl would’ve been nearly fifty at the time.It is a review for a tragedy draft authored by Carlisle, which he had privately published for his friends inspection: as a play, it has never been performed to my knowledge. Samuel Johnson noted that it was not very well suited for stage, given it’s lack of directions and arrangements – but he spoke highly of the prose, especially the decision not to make the Archbishop an object of scorn, ‘in defiance of prejudice and fashion’ of plays at the time. But it was certainly no Goldsmith or Dryden from his perspective.

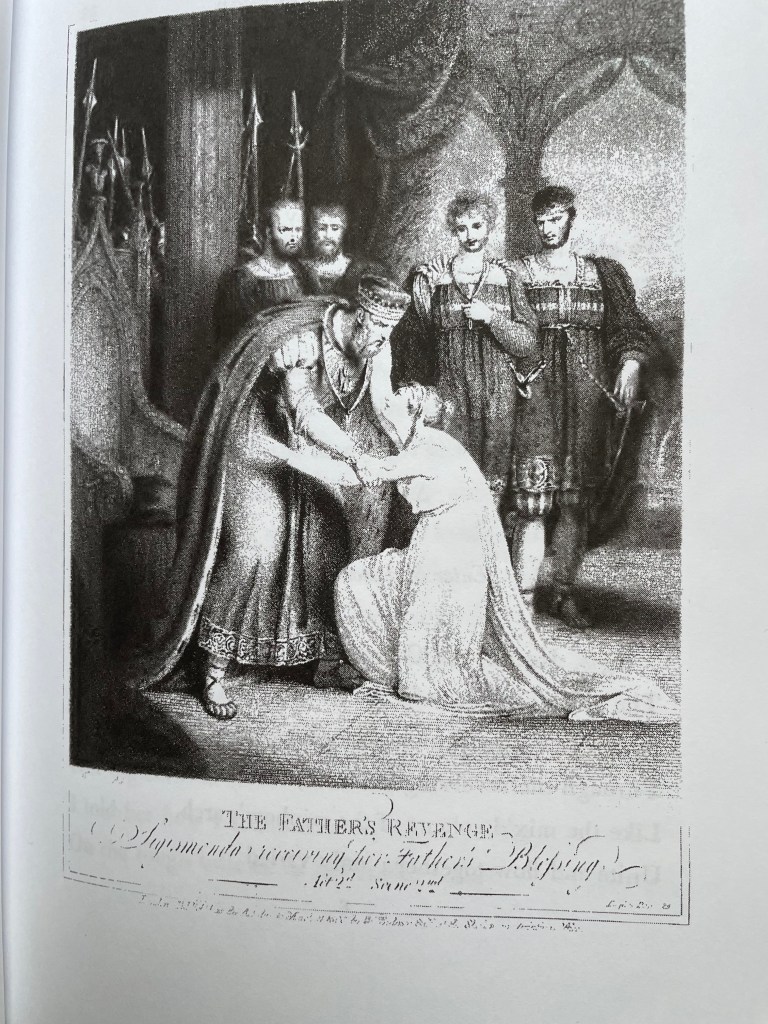

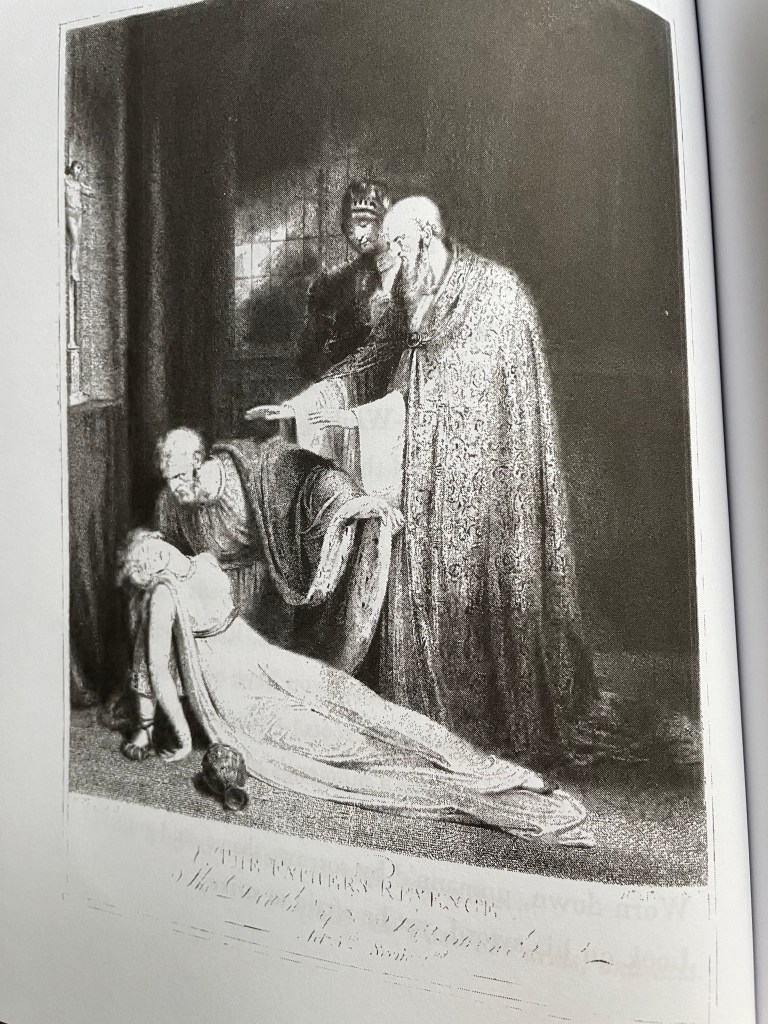

Though you cannot call me a theatre kid and I cannot stand poetry, I was struck by a whim to read the play when I saw it. I had a stroke of luck at Waterstones; turns out there were more copies in circulation than you’d expect! The collection I found, printed by the preservational Hustree Press – the frontispiece references an 1800 edition published by William Bulmer. It even comes with some nifty illustrations: I sadly cannot determine the artists name due to the illegibility of captions.

Synopsis – Spoilers from 88,452 days ago.

If you’ve read a lot of Shakespeare before, you can probably guess how this narrative is going to go. This is to be expected with a lot of enlightenment plays, when people did not view tropes with the same exasperation as people do today; writing was a lot more allegorical, with storylines meaning to teach rather than titilate. “A father’s revenge” is something of a mismatch between “King Lear”, “Romeo and Juliet” and a twist coming from “Winter’s Tale”.

Carlisle’s story concerns the ill-fated homecoming of the army-reared orphan Guiscard to Salemi in Sicily, then ruled by the tyrannical Tancred. Back from crusading, Guiscard has brought in his train an elderly Syrian (Hassan) and wishes to win the heart of Sigismonda, who happens to be Tancred’s Daughter. Guiscard thinks his laurels will make a fine enough dowry for his royal in-law, as well as a suitable recommendation to pardon Hassan from being a tool in a hostage crisis.

The very first thing we hear from the Archbishop (Tancred’s own brother) is that the man readily faciliates city-wide assassinations and tortures suspected rebels. His first line of dialogue is a blasphemous epistle about how seductive fame and fear are. He is also viciously overprotective of his daughter.

Guiscard was obviously too optimistic and genre-blind to realise where things were heading, especially as his immediate action is to join a coup against the king led comrades Monforti and Raymond. This plan involves a treacherous friar administrating anaesthetia to the palatial guard in a combination of Lady Macbeth and Lawrence’s ploy, then smuggling Sigismonda off shore in a boat – Monforti will be crowned king and Guiscard gets the girl, who is predictably a childhood friend who deeply reciprocates his love. She is sick of her domineering daddy forcing her to live the life of an involuntary celibate and like the modern incel specimen ends up getting a lot of hapless people killed when the plot is discovered.

Before then, though, Guiscard hears Hassan’s full tale, wherein he relates the loss of his dear wife and infant son, who evaded capture at sea by drowning herself. In a twist only possible in classical theatre, the baby evaded drowning and was picked up as a foundling on the calabrian shore: Guiscard the fair! A twist on the classical (and often racist) cliche perhaps, typically applied to beautiful maiden foundlings raised by Roma communities, but a welcome one: a tender moment ensues between father and son before Guiscard goes off to bugger things over at the harbour.

The whole conspiracy is arrested after a tipoff – Tancred has Sigismonda imprisoned in a convenient tower and prepares to execute the rest, starting with Guiscard after the lid is blown off his forbidden romance. Tancred decides impulsively to deliver guiscard’s heart to Sigismonda in a jar (prop – Pig offal). She goes insane and expectedly dies from grief, but not before forgiving her father like a good christian which serves to make Tancred feel even more awful. After moping about the repercussions of this father’s eponymous revenge, Tancred sees the wrong in his ways and decides to set grieving father Hassan free. Curtain call.

Analysis – Slopspear or Better?

Classical plays like this were already somewhat outmoded by the reign of Farmer George III, who had gotten over Middleton-styled slop and could only digest such works in the newfangled operatic mode. As a result, it’s no surprise that the work was never adapted as it failed to compete with the wildly bawdy and trendy “Newgate plays”, wherein highwaymen hammed it up and bedded multiple Sigismondas in one sitting before being hung.

That said, it is really not a bad Shakespeare pastiche. Carlisle really does come across as the sort of crusty fop who read the folio a thousand times over. The Iambic pentameter is there most of the time, as well as several keenly adapted plot points and a neat historical basis: the play is a somber adaptation of a story from the Decameron, which in itself has recieved a handful of historical adaptations. The storyline with Hassan is a nice addition, somewhat nudging stereotypes of the time that all muslims were oriental satanists.

The dialogue is fattened with decadent imagery: greek gods and anatolian poppies are evoked, meteors blaze through wintry nights, tyrants are abastracted into fortresses and not one bloody noun goes unmodified. I will concede that Carlisle can pull off some touching statements when he’s not clinging to conventions. Hassan, overwhelmed by the revelation that Guiscard is his son, utters the following lamentation:

“O Gods!

I could have borne my woes; that stranger Joy

Wounds while it smiles. The long-imprisoned wretch,

Emerging from the night of his damp cell,

Shrinks from the sun’s bright beams, and that which flings

Gladness over all, to him is agony.”

I agree with Johnson that this is an exceptional quotation for an amateur writer. It is not dampened in the slightest by my pathetic sympathy on dazzling myself turning on my sidelight awakening on a dark winter’s morning.

Criticising the play is a little more difficult; I could go all out with my subjective nitpicks of the conventions or highlight the use of character exposition instead of clear stage directions, as well as the fact that most of the action (bar Tancred raging at the Friar and the arrest) happens offstage. The main problem is, compared with even Shakespeare’s tragedies, there are no moments where the prose slackens to let the viewer digest what is being said. Every servant and side character speaks with the same stodgy gradiosity as the Archbishop, even when Manfred “(does) not want to cloak (his) meaning in ambiguous terms”. The constant salvo makes it difficult to appreciate some of the prosaic Peaks, forming a kind of indistinct plateau that doesn’t entrance the reader as much after the fiftieth evocation. A little straightforward small talk in some places wouldn’t necessarily throw off the sombre tone – could even amplify it if Carlisle allowed himself some individual voice rather than aping other polyglots or poets. He could also learn a thing or two from Goldsmith.

There is also some poetry by Carlisle in the play’s edition that I own which is absolute doggerel, going into paroxysms of hyperbole over the resignation of Joshua Reynolds and so on. It has to be read to be believed. This has nothing to do with the play, aside from a translation of Dante wherein the image of Ugolio devouring his sons (and later his adversary in hell) comes into the play.

Conclusion – Erring pity is for an erring man.

So what have I learned from reading this blutocrat’s vintage fanfiction? Quite a few new words I hadn’t heard before, for a start: Pestiferous is a good adjective for flatuence going forwards. On a more serious note, it can be revitalising to read obscure literature like this as it helps one concieve what the trends of a time were. Slop content didn’t come with AI – it started out with shakespeare ripping off older plays and passing them off as his own masterworks. And yet something apparently neglected by the ages can still have merits that codified crap does not. It’s worth diverging away from what we’re told to read by the historians and Tiktok to make out own discoveries in strange places. Even bad poetry can teach you new things. If we only read what we want to read, we don’t learn anything – we don’t grow as writers.

Buy this book on Waterstones for £13 instead of yet another crime novel by George Saunders. Change of scenery!

- This incident was in turn referenced by Sam Weller in Dickens’ first story “The Pickwick Papers”, wherein he speaks of an unlucky man who shot himself after being told that his beloves crumpets were the source of his gut troubles. ↩︎

Leave a comment